Approaches for throttling asynchronous methods in C#

Imagine you’re using C# and need to call an async method in a loop, like to download content from a given URI and perform some work on it. Our hypothetical method has the signature Task ProcessUri(Uri uri), and calling it in a loop might look something like this:

foreach (var uri in uris)

{

await ProcessUri(uri);

}

This loops over each URI in the uris collection and processes each one individually, one at a time. Most of the time waiting for this code to complete is likely going to be spent waiting to receive content. In other words, we’re going to spend most of the time doing nothing productive.

We don’t have to process each URI one at a time. Since ProcessUri is an asynchronous method, we can easily process them all at once in a single line of code:

await Task.WhenAll(uris.Select(ProcessUri));

Select projects the collection of URIs to an IEnumerable<Task>. Task.WhenAll takes this IEnumerable<Task> and returns a single Task that completes when all of the Tasks in the collection have completed. We’re now only awaiting this single Task. This will now begin to download all of the URIs at nearly the same time and process them concurrently.

What if we have a huge number of URIs to process? If we try to process 10,000 URIs at once, we could exhaust sockets and start getting SocketExceptions, or maybe run into rate limit issues if we’re making calls to an API. There are many reasons we wouldn’t want to try to process them all at once, but we don’t want to go back to processing them one at a time. Could we throttle the maximum number of URIs we process concurrently at any given time?

Parallel.ForEach

One approach I’ve seen people reach for when trying to throttle asynchronous method calls is to use Parallel.ForEach. This is intended for CPU-bound work, not IO-bound work which dominates asynchronous code. However, it can be shoehorned into invoking asynchronous methods concurrently. In order to work, the current thread must be blocked synchronously until the Task completes, such as by using the methods Task.Wait() or Task.GetAwaiter().GetResult(), or by getting the Task.Result property, like this:

Parallel.ForEach(uris, uri =>

{

ProcessUri(uri).Wait();

});

Don’t do this.

Don’t use Parallel.ForEach with asynchronous code.

Synchronously blocking asynchronous methods is an anti-pattern and should be avoided whenever possible. This will block the current thread, destroying the primary benefit of using asynchronous methods in the first place. A thread is now tied up dedicated to waiting for each Task to complete. Synchronously blocking Tasks can also cause deadlock. There are times when you need to do it, like when calling asynchronous code from otherwise completely synchronous code or at a top-level main method, but outside of those situations it should not be used.

Partitioner

Another approach I’ve seen is to use the Partitioner type, which can be nicely abstracted into its own extension method:

public static Task ForEachAsyncPartitioner<T>(this IEnumerable<T> source,

int degreeOfParallelism, Func<T, Task> body)

{

return Task.WhenAll(Partitioner.Create(source)

.GetPartitions(degreeOfParallelism)

.Select(partition => Task.Run(async () =>

{

using (partition)

{

while (partition.MoveNext())

{

await body(partition.Current);

}

}

})));

}

It generates N partitions where N is the maximum number of asynchronous methods to execute concurrently at a time. In our example, if we have 10,000 URIs and we only want to process 10 at a time, this would generate 10 partitions each with 1,000 URIs. Processing each individual partition is then similar to our first approach where we simply looped over every URI and processed each one at a time, except now this is happening for each individual partition and wrapped inside a single Task. If we want to throttle to only 10 concurrent calls, then this will create 10 partitions and 10 Tasks to pass to Task.WhenAll.

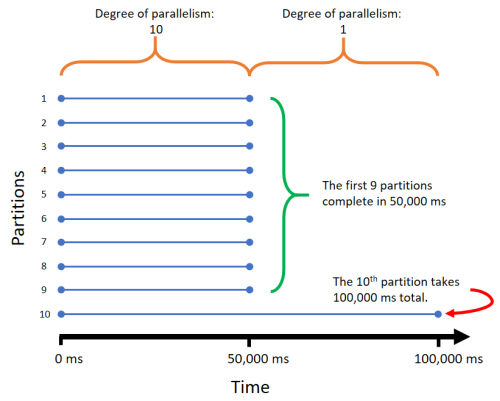

This is better than using Parallel.ForEach, but unless each Task takes the same amount of time to complete, then the given degreeOfParallelism value won’t always represent the degree of throttling. Going back to our example, imagine we have 10 partitions each with 1,000 URIs. Let’s say processing the URIs in the first nine partitions is very fast. Maybe the server returns a response quickly for those URIs, and the response size is small so we download it and process it quickly. Suppose the last partition processes very slowly, maybe because of slow response times and large responses. Specifically, let’s say the first nine partitions take 50,000 ms each and processing the last partition takes 100,000 ms. For the first 50,000 ms, we’ll be chewing through all partitions, processing 10 URIs at any given time. However, once the first 9 partitions finish at 50,000 ms, we’ll spend the next 50,000 ms processing URIs one at a time in the last partition, making the given degreeOfParallelism of 10 effectively 1 for half of the execution time! This is inefficient if we can support the full degreeOfParallelism at all times.

Here’s a diagram to visualize the first 9 partitions completing quickly, the 10th partition taking a long time, and how this affects the degree of parallelism:

After poking around online I’ve since found this approach is described in one of Stephen Toub’s blog posts.

SemaphoreSlim

To process the maximum given number of items in the collection at all times as closest to our desired degree of parallelism, we can use the type SemaphoreSlim. In .NET 4.5, SemaphoreSlim.WaitAsync and was added that enables us to keep our method entirely asynchronous and non-blocking. Prior to .NET 4.5, SemaphoreSlim.Wait was the only option and will block if another thread is currently inside the critical section.

A semaphore is like a lock with a count. The count indicates how many threads can be inside the critical section at any given time. This is a good fit for our situation where we want to only process a given maximum number of items at any time.

The code can again be nicely abstracted into an extension method:

public static async Task ForEachAsyncSemaphore<T>(this IEnumerable<T> source,

int degreeOfParallelism, Func<T, Task> body)

{

var tasks = new List<Task>();

using (var throttler = new SemaphoreSlim(degreeOfParallelism))

{

foreach (var element in source)

{

await throttler.WaitAsync();

tasks.Add(Task.Run(async () =>

{

try

{

await body(element);

}

finally

{

throttler.Release();

}

}));

}

await Task.WhenAll(tasks);

}

}

For each element in the collection, we asynchronously wait to enter the semaphore. Once we enter, we start a Task and release the semaphore only when we’re done. The call to Release adds to the semaphore’s count, allowing a WaitAsync call to return and for another thread to enter the semaphore. Keeping all the tasks in a collection and calling await Task.WhenAll(tasks) at the end ensures the last tasks have completed.

This approach is non-blocking and asynchronous, and will keep us at our desired degreeOfParallelism for the entire duration of the call. This addresses the two problems we saw with the previous two approaches.

I’ve needed to fix code that used Parallel.ForEach and Partitioner, and replaced usages of those methods with something similar to the above extension using SemaphoreSlim. After searching online, I realized there actually exists a very robust library, AsyncEnumerable, that uses SemaphoreSlim to provide similar extensions.

Conclusion

When throttling asynchronous methods:

- Don’t use

Parallel.ForEach. - Don’t use

Partitioner. - Use AsyncEnumerable.