Hacking your GitHub contribution graph to look more consistently productive than you actually are

Jerry Seinfeld, the comedian, has said the way to become a better comic is to write better jokes. To write better jokes, he said, write jokes every day. One technique he used to pressure himself to write jokes every day was to put on the wall a calendar with the entire year on it. For each day that he wrote jokes, he would mark that day with a big red X.

After a few days you’ll have a chain. Just keep at it and the chain will grow longer every day. You’ll like seeing that chain, especially when you get a few weeks under your belt. Your only job next is to not break the chain.

Don’t break the chain.

Software developers can adopt this advice to become better developers by writing better code. Instead of writing jokes every day, they can write and commit code every day. GitHub’s contribution graph provides a great way to link commit dates with a yearly calendar, showing a green square instead of a red X for every day there’s at least one commit.

Striving to commit every day to keep the chain going is a great way to build the habit of constant personal improvement and community contribution by learning and building every day. After all, your git commit history can’t lie, right? If your GitHub contribution graph is full of green squares, doesn’t it show to yourself and everyone else that you didn’t break the chain?

Hacking the chain

One of git’s useful features is that history can be completely rewritten, meaning you can hack your chain to trick yourself and others into thinking you’re more consistently productive than you actually are.

For example, you can easily change the commit and author date of the most recent commit by executing these two commands:

set GIT_COMMITTER_DATE="Mon Dec 19 19:14:10 2016 -0500"

git commit --amend --date "Mon Dec 19 19:14:10 2016 -0500"

Regardless of when the last commit was authored or committed, it will be changed to 7:14:10 PM on Monday, December 19th. The --date flag changes the author date, and setting GIT_COMMITTER_DATE will use the specified date as the commit date. However, changing a single commit at a time is annoying. If you have a lot of in-progress work you want to get to, constantly running this command after each commit is tedious. If you miss a day somewhere in your history, you can’t go back to fix it unless you rebase interactively. Keeping track of which commit you want to change to which date and setting GIT_COMMITTER_DATE between each call to git rebase --continue for many date changes in an interactive rebase is tedious too.

This seems easily automatable. We should be able to misrepresent ourselves more efficiently than this. If I could slap together a simple UI to specify dates, it wouldn’t be too hard to generate the git commands for all the dates in each of the rebase steps. I haven’t played around with interactive rebases very much, so I thought this would be a neat project to learn git rebase -i a little better.

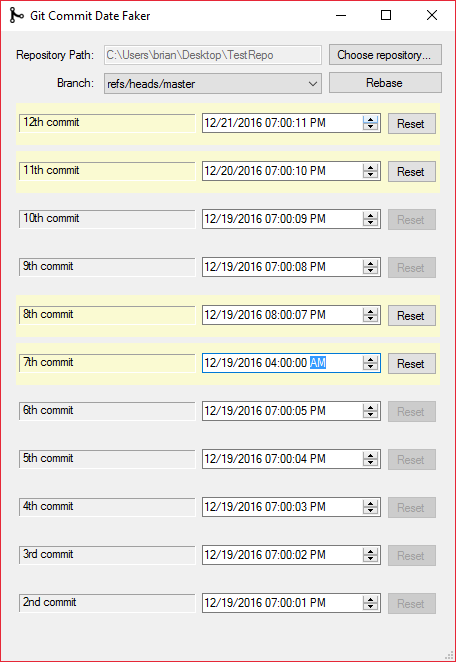

I tinkered with this idea and built a small Windows desktop app that given a path to a valid git repository will give you a list of the last 100 commits for each branch. For each commit, you can edit its commit and author date using the date picker next to each commit. When you push the rebase button at the top it will run an interactive rebase to change the commits to use your supplied dates.

The code for this project is here.

I thought I could do this entirely in LibGit2Sharp, a wrapper around libgit2. Unfortunately only the pick option is supported in interactive rebases, and I need edit. If edits were supported in rebases I could’ve written a tool that, through Mono, would be completely cross-platform out of the box. Since edit rebase operations are not supported, for now I send commands to cmd.exe to run batches of commands to the git on the system path. If I detect that the platform is Linux I could probably swap these out with bash calls in the future.

Don’t actually do this

A long time ago I tried not to break the chain when working on the exercises at the end of each chapter of the book Scala for the Impatient. I didn’t always succeed. About one or twice a week I’d miss a day and there’d be a sad empty square on my GitHub contribution graph. I used the commit --amend --date command a few times and felt pretty proud of myself for figuring out a way to fill out those sad empty squares with happy green.

But to what end? I wasn’t actually able to do it. Do you think Jerry Seinfeld got to where he is by skipping some days, writing a few extra jokes, and figuring it was enough that he could backfill red Xs for a few days? No. It’s a lie, and it defeats the point of trying to build the habits to become a better comic, a better developer, or a better craftsman regardless of the skill.

It takes work. Real work. A few commits spread thin over a few more days isn’t going to fool anybody, especially in my case when it was a few lines for exercises out of the back of a book. Superficial work spread out over a few days is still superficial. If you build something of real merit or technical complexity, then its value will stand on its own. Whether it occupies three or thirty green squares is irrelevant, and anybody who can recognize its value will be able to see through that.

It can also become an unethical misrepresentation of yourself. If you associate your GitHub identity with your real identity and showcase your GitHub contributions to try to impress others, such as to impress an interviewer into hiring you, then your contributions become an extension of your resume and the qualifications you signal that you possess. If you wouldn’t lie on your resume, don’t lie on your contribution graph. However, I’d also argue that since building anything of value still takes real work, then the act of spreading out commits to create the perception you’re able to work more often or more consistently than you actually are is really only a misrepresentation of your ability to manage your time. That doesn’t change the nature of the act, but it would change the scope of the misrepresentation.

Just don’t do it, OK? Unless it’s to draw pretty pictures.